Location of the castle

The contours of the neo-gothic building rise more than about 330 ft above the river Moselle on an outstanding hill. The silhouette of the towering hill seems to continue in the building which is topped by the slate roof of the massive keep. As for its structure, Cochem Castle belongs to the category of castles protected by height that had to be protected all around. Romanesque fragments found in the well indicate a reinforcement of the castle around 1056.

Around this time or a bit earlier the core of the Romanesque square keep (17ft by 17ft) was built, its walls being up to 12ft thick. At the same time, the keep was also made higher. In the first half of the 14th century, archbishop Balduin of Trier connected the castle and the town by massive walls. Furthermore a chain was installed below the castle to form a removable toll barrier across the river.

History of Cochem Castle

It is generally assumed that Cochem Castle was built around the year 1000 by the palatinate count Ezzo, son and successor to palatinate count Hermann Pusilius. The castle was first mentioned in a document in 1051 when Richeza, Ezzo’s oldest daughter and former Queen of Poland, gave the castle to her nephew palatine count Henry I. Even when Ezzo’s family ceased to be palatinate counts, Cochem remained connected to the title of the palatinate counts. Years later, in 1151, king Konrad III put an end to a dispute concerning the succession by occupying the castle with troupes. Like this, he finally took control of the castle, which became an imperial fiefdom. Thus, Cochem became an imperial castle in the time when the Staufer dynasty reigned in Germany. From this time on, imperial ministers – with the title of “Lord of the castle” – were installed to administer the castle and the surrounding properties.

In 1294, king Adolf of Nassau pawned the castle and the city of Cochem as well as the surrounding imperial property of about 50 villages to Boemund I of Trier in order to pay for his coronation as German emperor. But neither Adolf nor his successor, King Albrecht I of Austria could redeem the pledge. For this reason the archbishops of Trier kept Cochem as a hereditary fiefdom until 1794. Under the reign of Archbishop Balduin (1307-1354) the old castle was enlarged and fortified. From 1419, the Lords of the castle were replaced by local magistrates.

When the troupes of King Louis XIV (called Sun King) invaded the Rhine and the Moselle area in the war of succession of the Palatinate, Cochem castle, too, was occupied in 1688. After the town had been completely occupied by French troupes in March 1689, the castle was set on fire, undermined and blown up on May 19th of 1689.

The French Sun King’s troops almost completely destroyed the town of Cochem. The castle remained in ruins until 1868, when a Berlin business- man, Mr. Louis Ravené, bought the castle grounds and the ruins. Shortly after his purchase he began to rebuild Cochem Castle incorporating the remains of the late Gothic buildings into the main castle structure.

The entire structure was rebuilt in the then popular Neo-Gothic architectural style. This style corresponded to the romantic ideals in vogue in Germany in the 19th century. The trend at the time throughout Germany was for nobility or other wealthy persons to purchase and refurbish castle ruins as family summer residences. The Ravené family followed this trend and used the castle as a family summer residence.

Today the castle is still well-equipped with Renaissance and Baroque furniture, which was carefully collected by the Ravené family. Since 1978 the castle has been owned by the town of Cochem and is run by “Reichsburg Cochem Ltd.” Cochem Castle, situated on an outstanding hill more than 100 metres above the river Moselle, is a popular tourist attraction.

Louis Ravené

The Huguenot family originally came from Metz and came to Berlin in 1685 as religious refugees. The family ran a brass and bell foundry. The Ravené Company had its origins in the iron trading company Samuel Gottlieb Butzer which was founded in 1722. Jakob R. married the daughter of the iron trader on 14.08.1775. After the death of his father-in-law in the same year he took over the business.

In 1824 Jakob R. signed the business over to both his sons and his son-in-law. His son Pierre took on the running of the business on his own in 1833 and under his management the renowned business became a wholesale company. His son, the erector of the castle, Jacob Louis Fredéric R. had a large active share in the rise of the company under his father’s management, he then took over the control of the company and enlarged it. He married Therese Elisabeth Emelie von Kusserow in 1864, who bore him three children before falling in love with a house guest called Gustav Simon.

She was separated from her husband in 1874. Although he wanted to save their marriage, he did not succeed. He died in the Czech spa resort in 1879.

Not so many years after Ravené’s death Theodor Fontane read in the newspaper about the auction sale of Mr Ravené’s plant collection and wrote a novel called “L’Adultera”. He based the novel’s character van der Straaten on Mr. Ravené. In 1854 Ravené received the 4th class red eagle medal. The title of councillor of commerce was bestowed on him in 1862. He was an honorary citizen of the towns Ilmenau in Thüringen and Cochem. An imported palm from the Comoro Island Johanna was named after him in 1879 as palm Ravenea Hildebrandti.

Not so many years after Ravené’s death Theodor Fontane read in the newspaper about the auction sale of Mr Ravené’s plant collection and wrote a novel called “L’Adultera”. He based the novel’s character van der Straaten on Mr. Ravené. In 1854 Ravené received the 4th class red eagle medal. The title of councillor of commerce was bestowed on him in 1862. He was an honorary citizen of the towns Ilmenau in Thüringen and Cochem. An imported palm from the Comoro Island Johanna was named after him in 1879 as palm Ravenea Hildebrandti.

His son, Dr. Louis Ferdinand Auguste Ravené was 12 years old when his father died. He took on the family business in 1887 and in 1888 he married Martha Helene Wilhelmine Ende in Berlin, who was the daughter of the family architect, Hermann Ende. After his wife died he got married for a second time to Elisabeth Cäcile von Alten.

He died in 1944 in Potsdam. His grave is to be found alongside that of his first wife’s in Marquardt, a district of Potsdam.

The reconstruction

In the course of the planning the construction of a railway line between Koblenz and Metz along the Moselle, our region attracted the interest of Ravené and he fell in love with the ruin of Cochem castle.

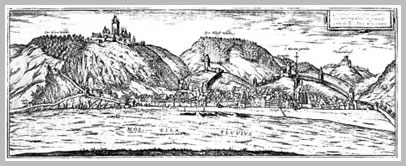

Together with the government building officer Hermann Ende, Ravené put in an application already at the beginning of 1867 to the Prussian area administration in order to buy the ruin and rebuild it. About one year later in 1868 the then Prussian King Wilhelm I authorized the sale on the following conditions:

- The preservation of the standing ruins and the reconstruction according to historic parameters (copperplate brown and Hogenberg)

- Authorization of the building plans by the Minister for science and culture

- Partial opening of the castle for the public

- Pre-emption right of the state

The sum of 300 Talers was a symbolic price, they orientated themselves on a similar case – the sale of the ruin Hammerstein.

In June 1868 under the direction of Professor and royal building officer Ende, they started to clear away the huge piles of debris, and uncovered and secured all the foundation walls, and the foundations as well as cellars on the Moselle side of the castle and the castle well. The castle was rebuilt on top and the highest rooms were furnished for the constructor.

As from 1871 the second part of the reconstruction was started under the direction of building officer Julius Carl Raschdorff. Building officer Raschdorff was known for renaissance buildings (the Wallraf Richartz, museum in Cologne) he had previously been town master builder in Cologne and had already acquired an excellent reputation.

The planning of the exterior was kept in accordance with the conditions of sale. The sketched plans from the architectural drawing book are still available today. The planning of the interior was also left to Raschdorff, however these sketches were not passed on down to us today.

The interior design was assigned to Prof. Ernst Ewald from Berlin. He designed the intricate painted decoration on the ceilings and the walls on the inside and the outside. The poker work he carried out either himself or had his employees Göthe and the painter Münster from Cologne do it for him. But local artists and craftsmen also played a part. The rooms are accordingly decorative and the furniture is appropriately comfortable. The old styles of building were taken into consideration, which had been used in its one thousand year old history.

SConsequently our guests today during the guided tour will come across, amongst other things, a dining room in Neo-renaissance style, a gothic and a Romanesque room. In 1877 the inauguration of the castle and the opening of the Emperor Wilhelm railway tunnel were celebrated with a banquet in the knight’s hall in the castle. High ranking guests were present. The seat next to Mr Ravené, however remained empty, as his wife had left him.

Legends around the castle

The battle of the barrels

We are in Cochem castle. The year of its construction dates back to 1000 AD. The castle was a medieval structure of defence like other knights’ castles but maybe a little nobler as it housed the counts of the Palatinate along the Rhine who were related to the German Emperors, at the time when they were all called Emperor Otto. The history of the castle ranked itself seamlessly in the social fabric of its time with its intrigues and battles of power. Favourable marriages increased the powers of the powerful. But also murder and manslaughter were common, in order to assassinate disagreeable fellow men and rivals.

And so it came to pass that in 1062 Countess Mathilde of the Palatinate had the death of her husband on her conscience or for instance Count Hermann of Salm and Luxembourg, former German King, accidentally stoned to death the vigilant damsel of the castle in 1086. The counts of the Rhineland Palatinate – their territories wedged between the archdioceses of Cologne, Trier and Mainz – left the Moselle region and took up residence, from then on, in Heidelberg. The Prince of the Electorate and Archbishop of Trier used this opportunity to unite the Archdiocese Trier with Koblenz. Cochem Castle became an administration centre, the Moselle region was, on the whole, spared of various wars and the people of the Moselle were fond of saying “life is good under the rule of the hooked staff”.

It was however never entirely peaceful in the German states. The Knight Franz of Sickingen and his troupes drew in on Trier. The Prince of the Electorate called on the people of his electorate for help. From Cochem and Zell 386 armed men marched hurriedly to Trier. You have to credit them for their bravery because Knight Franz gave up the siege and withdrew. However his troupes, enraged by the lost chance of a victory, took out their anger on the Moselle villages.

One of these mobs approached Cochem. When they saw the town’s gates were barricaded they camped out on the meadow by the Endert stream and prepared themselves to storm the town. The councillors of Cochem, who had to organise the defence of the town, were in dire straits. Then one of them had an idea. They ordered everyone to roll the empty wine barrels up to the Endert town gateway and to pile them up high. As the ramshackle mob began to storm the town the next morning, they pushed over the pyramid of barrels. The barrels rumbled and tumbled down the hill straight into the ranks of the attackers. They were oppressed and crushed and withdrew. They thought, of course, in a town with so many empty wine barrels, there could hardly be any full wine barrels left to loot!

The people of Cochem still tell the tale today, over a round of drinks, about their cunning ruse back then and the victory of the battle of the barrels!

“Knipp Monday“

There is supposed to have been more than 40.000 Knights’ castles at one time in the German speaking part of Europe. They were the fortified bases of powerful people. They reported back on movements of troupes in their areas and were supposed to be able to fight small conflicts until the local lords summoned together enough troupes for a battle.

Such a surprise attack on Cochem castle was uncovered by a castle servant, who was riding along on high ground up in the village of Faid on “white Sunday” (the 1st Sunday after Easter) on his way to visiting his sweetheart. He encountered armed strangers and heard about their planned attack on Cochem castle. The servant galloped away immediately back to the castle and raised alarm. The men at the castle armed themselves ready for defence. The next morning when the mob attacked the castle they ended up beating a speedy retreat with bloody heads.

The lord of the castle was very grateful to his men for their vigilance and bravery, he gave them the day off work and declared the Monday after “white Sunday“ to be a public holiday for the people of the castle and the town for evermore.

Since then the people of Cochem make their way, with baskets full of food and jugs full of wine, to a meadow by the name of “Knipp” just above the castle where the attackers had prepared their assault that time. They eat, drink, sing and make merry and the young people make up for what the servant and his sweetheart had to go without on that day back then!

They celebrate every year since then “Knipp Monday”.